Section 63: Powers to remove persons attending or preparing for a rave

“This section applies to a gathering on land in the open air of 20 or more persons (whether or not trespassers) at which amplified music is played during the night (with or without intermissions) and is such as, by reason of its loudness and duration and the time at which it is played, is likely to cause serious distress to the inhabitants of the locality”

This piece of criminal legislation was introduced in 1994 by the British Government to restrict the size and number of raves. The establishment desperately don’t want us to party, yet we still do; we always will, it’s in our blood. Since the passing of this bill, rave culture has grown and grown, becoming almost infectious across the world. Yet, it has changed drastically since it’s beginning, with the likes of ‘Burning Man’ festival becoming almost unrecognizable to its origins within the dark, dinghy warehouses of the UK. Whilst the American rave scene may be drastically different in an aesthetic sense from the UK’s, the purpose is still the same; to rebel and to escape.

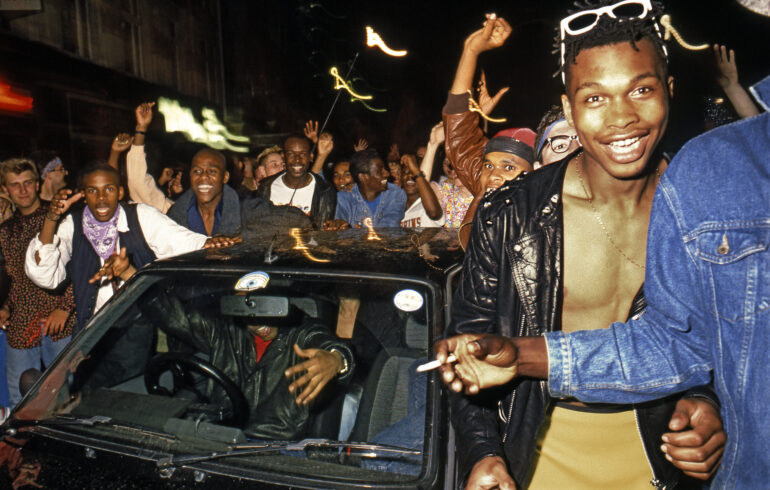

Before I delve into the resurgence of the rave scene within the modern generation and its subsequent evolution, I think we must first look back at its conception. Born out of the gloomy, sweaty basements and warehouses across the United Kingdom the rave scene was originally a counterculture icon. It didn’t care about the glitz and glam of other musical genres, its niche characteristic was that individuals defied control from government authority. The act of partying in this kind of self-indulgent fashion originates from a point of rebellion, a behavioural trait that will never disappear. Ultimately, the UK rave scene was conceived as a middle finger in reaction to Thatcherism, and thus, the establishment. Margaret Thatcher’s political philosophies of free markets within the 80s and 90s were the match that set the rave scene alight. Low taxation, privatization of state-owned industries, and a retrenched welfare state lead to a decreased role of the state in the everyday lives of citizens. As a result, this created winners and losers, with the losers falling victim to the brutal free market. It was these ‘Losers’ that constructed the rebellious act of raving allowing them to use the creative expression of partying to deal with the social calamities. Rave culture began as a way for marginalized communities to forget about the high unemployment and hopelessness that they faced. It provided a feeling of escapism like nothing else; constructing a lawless space on the fringes of society where people flocked to forget the monotony of the 9 to 5 and transcend to a place free of judgement and responsibility.

Almost instantly this subculture of music became contagious, as it exploded throughout societies across the UK. Genres like Techno, Acid House and Jabber stormed into the charts with no regard for the rules. Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s electronic anthem “Jack Your Body” climbed to the top of the charts in the UK during 1987. Underground DJs also began a meteoric rise into popularity such as Carl Cox and Nicky Holloway. Rave culture was entering the mainstream and Politicians couldn’t stand it; people were having fun, how dare they!

Newspaper headlines started to follow suit as they grabbed public attention by decrying the bacchanalia and hedonistic behavior of ravers – especially their drug usage. The Newspapers worked in tandem with Politicians to portray ravers as ‘the problem with Britain’ and thus, frame the rave scene as inherently disorderly. Nobody wanted the ravers to party, and with the passing of the previously mentioned ‘Section 63’ the law supported this oppressive desire. Nevertheless, it was the establishments’ hatred for the culture that fuelled the youth’s love for it. In recognizing rave culture as rebellious and attempting to control it the Government only accentuated the culture more. Ravers now had a purpose to party into the early hours; to piss everyone off. In being labelled a societal problem it only emphasized a new characteristic, that of rebellion. Thus, raving became more than just a genre of music, it became a whole revolution constructed around the idea of true liberty. The adrenaline pulsing throughout a raver’s blood comes from that feeling of illegality (and perhaps some cocaine). In the words of actor Peter Fonda, “We wanna be free, and we wanna be free to do what we wanna do”, and rave culture provides precisely this libertarian release. On the dance floor of some random Sweatbox in London, two-stepping to infectious electronic beats, surrounded by drug-fuelled individuals, is weirdly one of the few places we can find authentic liberty.

These characteristics of independence and insurgency resonate strongly within youth culture. Because of this ideological connection between the demographic and the genre, rave culture has experienced unprecedented growth within both the youth of the UK and America. Aesthetically the UK scene has stayed fairly close to its roots. Events such as Warehouse Project and Printworks keep the spirit of 90s rave culture alive whilst giving it a modernized coat of paint. Warehouse project especially seems to pay homage to the earlier days of raving as it oozes love, escapism and piss ups. You look through the crowd at WHP and you will see everything the government hates; lads dressed in “menacing” all black, girls in supposedly “distasteful” tight clothing and keys dipping into mountains of class As. It’s the epicenter of modern-day rave culture. The lineups seen at such events are reminiscent of early acid house and techno, through the likes of Bicep and Annie Mac. However, we have recently seen a musical diversification towards the contemporary scene through performances from Grime artist Skepta and Hip – Hop star Joey Bada$$. Despite the UK scene perhaps modernizing into newer genres, the venues don’t forget the classical scenes of the 90s. In walking through the gates of Warehouse Project you seemingly escape reality as you proceed to pass back down the corridor of time. The sky-high ceilings and red brick walls seem to reverberate tales of a previous era. Even away from the huge, flashy events, the ideology of rebellion lives on. It’s almost a rite of passage for the 16-year-old English lad or girl to sneak out to get blackout in a park or friends house. Across the country, news reports have confirmed illegal raves every weekend over the past few years. Despite being decades apart, the contemporary scene has not forgotten where it came from. A rebellious nostalgia has been passed down through generations, catalyzing our need to be free.

If a Brit was to gaze across the Atlantic, they would witness a very different type of rave culture, one which they may perceive as “weaker” and “vainer”. Yet in reality, the American scene is just as electric, it’s simply a different kind of energy. Within a visual sense, the two scenes drastically juxtapose each other. The UK attempts to go back in time, whilst the contemporary American rave looks closer to the inside of a spaceship than the inside of a warehouse. This antithetical aesthetic has developed due to the different musical genres at work here. By far the most popular genre within the American scene is the global sensation of Electronic Dance Music (EDM). Personified by booming rollers, high pitched electronics and astronomical energy; it’s no wonder that American raves feel otherworldly. In order to mirror the cosmic pulsations of EDM, many rave festivals incorporate lights, lasers, projections, and fireworks to support the celestial motifs. On the surface layer, the two rave scenes couldn’t seem further apart, yet in reality, the core purpose of raving is still there. We could visualize the different scenes as two sides of a coin; the same but different. The construction of alien-like festivals, such as ‘Ultra Music Festival’ in Miami, creates that same type of escapism at the heart of early rave culture. In fact, it could even be seen as amplifying it to the next level. What better way to forget about your everyday problems than to enter a space of worldly transcendence?

Furthermore, those rebellious aspects still persist, just within ways more akin to hippie culture. One of the phenomena of the American scene is that of ‘Kandi’ bands. A bracelet like item, engraved with messages of peace and love, which are exchanged between ravers in an act of respect. This ritual of exchange is named P.L.U.R; an acronym for Peace, Love, Unity and Respect. It’s perhaps easy to see why the experienced British raver would frown down on essentially trading bracelets within a rave, however, the rebellious intentions can be seen shining through. These messages of peace and love become reminiscent of the original hippie counterculture. Hippies of the 1960s rejected the establishment, government oppression and ultimately mainstream American life. Instead, they preached messages of unified love and sexual liberation. Through the P.L.U.R philosophy that the American raver uptakes them too preach these values of rebellion. For brief moments they can leave behind the controlling establishment and live within a space of total harmony, similar to that of the hippie revolution. Thus, whilst visually antithetical the purpose of the American and British rave scene remains the same.

Red Stripe. North Face. Jumping fences. Strobe lighting. Repetitive music. It’s a universal language. A language that brings people together from all backgrounds to forget life’s worries and to rebel against the rules, whether it be for a day, a night or a weekend, ravers will always find a way to keep the party going.